A Revolution is Not a Dinner Party

– Mao Zedong

Alarmists decry the “secret Farm Bill,” although the failure of the Joint Select Committee on Deficit Reduction has now rendered it moot except possibly as an example of the surprising notion that politicians can occasionally work in a bi-partisan and bi-cameral fashion on America’s own version of the Five-Year Plan. Optimists note the increasing numbers of young people going back to the land and re-learning the simple arts of growing, cooking, and preserving food. In Fair Food: Growing a Healthy, Sustainable Food System for All, Oran Hesterman writes that the fair food movement may be the movement of this young generation, much as the anti-Vietnam War movement engaged the youth of the late sixties and early seventies. Can it be that America is indeed entering into a good food revolution that moves beyond the elitist foodie-dominated dinner party?

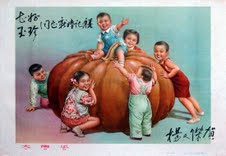

It was with a sense of serendipity, then, that I read about a new Chinese cookbook: just in time for the holidays, The Cultural Revolution Cookbook, by Sasha Gong and Scott D. Seligman, is available from Earnshaw Books. Full of colorful socialist realist art and notes and stories from the Cultural Revolution, this book has accomplished what few memoirs, histories, and movies about the era have done – present a reflective, thoughtfully balanced view of what has largely come to be viewed as an experiment that my ‘tween daughter’s generation would label “an epic fail.”

Sasha Gong was herself one of the many youth who were “sent down” to the countryside during the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution of 1966-1976, removed from city life to work and live with (and, Mao hoped, learn from) the peasants. There are plenty of accounts of this era that dwell on the horrors of life in poverty, of stretching flour with sawdust to make enough bread to survive, of the government manipulating the media to cover up famine statistics. Ironically, wasn’t there just a piece about American fast and processed food industries using cellulose – AKA wood pulp – as a filler and binder in their products, and wasn’t there a take-down notice on another site that posted the story?

But back to The Cultural Revolution Cookbook, which takes the stance that while in retrospect, many of the sent-down youth came to view the era as “a tragic waste of their productive years and an unmitigated disaster for China,” the truth of the matter is that many of these young people went willingly and enthusiastically, ready to do Mao’s bidding in whatever project would build the new socialism. And in fact, these youth learned a great deal about life skills, particularly about cooking. The ability to make do with what was available created a generation of cooks able to turn what was local, fresh, and seasonal (if scarce) into dishes that provided enough nourishment to get them through the arduous physical labor required of them.

This, then, is the starting point for the recipes in this book – a limited number of readily-available ingredients, simple substitutions, and straightforward instructions – and in this the authors have been highly successful. Anyone intimidated by the idea of cooking (much less cooking something as exotic as Chinese food) will find this cookbook invitingly simple, and I am all for cookbooks that reintroduce the average American to the kitchen! Additionally, with its colorful art, entertaining and informative sidebars, and attractive food photography, this book would serve equally well as a cultural artifact and coffee-table book.

On to the cold hard facts: with a friend’s help, I tested 11 of the book’s 60 recipes twice, served them to dinner guests, and have the following comments:

- Nine of the 11 recipes were resounding successes – they delivered exactly what the authors promise: simple foods simply prepared with tasty and attractive results. It was heartwarming to hear my leftover-averse ‘tween promise her friend that she’d bring the leftover “Sweet and Sour White Radish” (enough for both of them!) for lunch on Monday. Only one dish, the Vinegar-Glazed Chinese Cabbage, earned the comment, “Well, if my mother made this, I would eat it, but I wouldn’t like it!” (My Chinese-born husband, however, says that the dish is “the real thing.”) And only one dish, the Minced Pork and Scallion Cake, was much more problematic: the instructions omitted mincing the scallion, the amount of water added is truly excessive – it would seem 1 T is more appropriate than 1.5 c), and even an estimate of the amount of time to steam was not provided. This recipe, however, seems to be an exception: while I did not test more recipes, reading through all of them as someone who has studied culinary arts, I got the sense that they would largely be successful.

- The ingredients are wonderfully limited in number, and most of them are whole, close-to-the-source foods (the only minimally processed items were soy sauce, vinegar, canned stock, and tofu). I was a bit taken aback by the amount of sugar used and reduced it in all recipes the second time around.

- The substitutions suggested are mostly helpful, although I think telling the average American home cook that “any wine will do” may result in some Cabernet replacing what really should be more of a sherry-type wine.

- The instructions are simple to follow, particularly if you read the prefatory sections on utensils and portions. I would have liked to have seen a bit more clarity on procedures that can make or break a dish, such as “boiling” when “simmering” would be more appropriate, and I was surprised to see the microwave called upon a few times – not because it’s an anachronism, but because there are other, simpler ways of heating tofu and making it easier to handle. Completely as a matter of personal preference relating to ease of use, I would rather the instructions be presented as a numbered list than as a paragraph. In general, it’s as though your mother or grandmother is teaching you to make a family favorite (including, sometimes, the sense that you should do it that way just because she says so!) A more curious student might wish for a bit more explanation of the “why” alongside the “how.” And while I followed the recipes exactly as written the first time through, I balked at the all-too-frequent instruction to heat the oil to smoking – while it may be the way Chinese cooks have done it for centuries, my American sense that heating the oil to the smoking point may render it unhealthy overruled my desire to follow the directions.

In summary, from professional chefs (who will likely make tweaks as they go) to the average or aspiring home cook (who follows recipes to the letter), this book has a lot of food for thought as well as for cooking and enjoying with family and friends. I would not hesitate to recommend it, whether it’s for your own use in the home kitchen, as a gift for a fellow or aspiring cook, or for someone who has an interest in the Cultural Revolution period of modern Chinese history.

Thanks to the authors for providing the photos!

Filed under: cookbooks | Tagged: Chinese cookbooks, Cultural Revolution, Cultural Revolution Cookbook, Sasha Gong, Scott D. Seligman |

Leave a comment